THE DREAMING SERIES RANGE

HUNTER & TUCKER

ABOUT HUNTER & TUCKER

FOOD & WEAPONS

ABOUT FOOD & WEAPONS

ABORIGINAL TUCKER

ABOUT ABORIGINAL TUCKER

DIDGERIDOO MAN

ABOUT DIDGERIDOO MAN

GATHERING SEAFOOD

ABOUT GATHERING SEAFOOD

AUSTRALIAN EMBLEM

ABOUT AUSTRALIAN EMBLEM

WORMCATCHERS

ABOUT WORMCATCHERS

TWO CULTURES

ABOUT TWO CULTURES

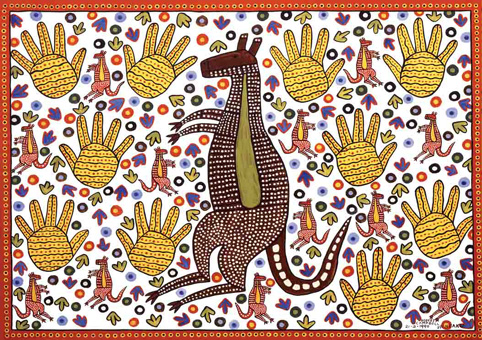

KANGAROO

ABOUT KANGAROO

AUSTRALIAN WILDLIFE

ABOUT AUSTRALIAN WILDLIFE

PLATYPUS

ABOUT PLATYPUS

GIVER OF LIFE

ABOUT GIVER OF LIFE

ABOUT THE DREAMING

Far back. Away in the deep mists of time. The seas and oceans existed. But the land was bare of any feature.

Far back. Away in the deep mists of time. The seas and oceans existed. But the land was bare of any feature.

The world was quiet.

Awaiting the beginning of life. That beginning came as the Spirit Ancestors of Creation. They are the ancestors of all life to come. There the spirit ancestors arose from the earth, And stretched their spirits out to cover the world. As they traveled this new world,

Hunting, gathering and making love with the earth.

They created all features of our world;

RIVERS AND MOUNTAINS – CLOUDS AND RAINS – ANIMALS AND PLANTS – THE MOON AND THE STARS.

Then they created humans,

TO LIVE TOGETHER IN THE WORLD WITH THE CREATION ANCESTORS.

With their acts of creation complete . . .

The spirit ancestors withdrew into the landscape of their creation;

Into the plants and animals. Into the waterholes and rivers. Into caves, rocks and mountains.Into the sun, moon and stars.

AND ALL WERE FREE TO ENJOY LIFE.

“Aborigines have a special connection with everything natural. We see all things natural as part of us. All the things on earth we see as part human. This is told through the idea of the Dreaming.” Quotation:Silas Roberts, Chairman of the Northern land Council. 1977.

This is a small part of the tale of the Great Spirit Ancestors of the Dreamtime.

The Ancestors are the source of the spirits of all souls. It is from the relationship with the spirit ancestors that traditional aborigines build an understanding of history, community, family ties and their own sense of individual being.

The Dreamtime does not refer to a state of dreams – but a vision of life from its very beginning and after its end. That part of life where faith and imagination makes the life we all dream of. The Dreamtime is a collection of thousands of myths and legends, all of which weave together to create the basis of life for the individual and for society. The Dreamtime explains how people are of the same life-force as the earth, the seas, the sun and stars.

The Dreamtime is a collection of thousands of myths and legends, all of which weave together to create the basis of life for the individual and for society. The Dreamtime explains how people are of the same life-force as the earth, the seas, the sun and stars.

Over 40,000 years new myths and tales were added to the Dreamtime, and different tribes developed their own tales of life. These tales are based upon the spiritual force of the ancestors, describing the relationship between people and all that exists on earth.

Aborigines sought to understand the way that all things in nature got along and focused less on themselves as humans than what we do nowadays. Keeping harmony in nature was the main aim of traditional society. Tribal authority and law was interpreted through the myths of the Dreamtime and was maintained via a complete social structure from which the tribe was built.

Aborigines sought to understand the way that all things in nature got along and focused less on themselves as humans than what we do nowadays. Keeping harmony in nature was the main aim of traditional society. Tribal authority and law was interpreted through the myths of the Dreamtime and was maintained via a complete social structure from which the tribe was built.

Myths are created to describe the laws of the society. The acts of goodness and evil are explained through tales of life in the universe. It may be a story of a man or a woman, an animal, a tree, the moon or the stars. But all myths tie back to the creation ancestors, and logic and reason was understood in terms of a natural harmony and order.

Each tribe weaved together their myths and legends to create a system of education and learning. The interdependence between the myths allowed traditional society to develop a complete learning process.

Each tribe weaved together their myths and legends to create a system of education and learning. The interdependence between the myths allowed traditional society to develop a complete learning process.

The Dreamtime puts great importance on harnessing the spirit and soul of each individual. The family unit was seen as the key to happiness. For aborigines, the family comprised the entire tribe, and thus each individual was an intricate member of an entire community. For an aboriginal child in the traditional life, every female member of the tribe who had given birth is that child’s mother.

Although every tribe developed their own unique versions of the Dreamtime, all tribes shared in common the creation ancestors., The legends of their creative acts have been passed down by aborigines through many hundreds of generations. These ancestors provide the basis for the emotional connection the aborigine has with the land.

They are the source of the spirits alive in all things and the creative force guiding our lives.

The Dreamtime is also a rich tapestry of ancient Australian history.

It describes now extinct animals such as the diprotodron, that roamed Australia 20,000 years ago. It recounts the event of an erupting volcano, (Mount Wilson, in the Blue Mountains, NSW).

It recounts the end of the ice age – 10,000 BC, when the world ‘reheated’, and global temperatures rose 5-10 degrees. The sea level rose 60 miles in Australia, and it was at this time that Tasmania and Papua New Guinea were separated from the mainland.

It tells of the rise of the great spiritual rock, ‘Uluru’ – great tales of storms, battles of ancestors, ravaging the land. Where by the forces of nature the ancestors represent came Uluru –

The world’s greatest monolith that exists on the surface of earth.

Within the Dreamtime, an Aborigine still in contact with the traditional life will be tied to the Creation Ancestors through his or her “dreaming” . The Dreaming to an Aborigine is the relationship with another part of nature that is also connected to the same particular spirit ancestor of creation. It may be;

A spirit ancestor of animals – a dingo, a bandicoot, emus, koala.

A spirit ancestor of the earth – a river, waterhole, rock, mountain.

A spirit ancestor of the sky – a star, the moon, the wind, sunset or sunrise.

The specific ancestor is a symbol of the human spirit of each aborigine – it is the place of origin of their souls and symbolizes their nature. An aborigine develops their sense of identity from observing the nature and character of their Dreaming totem. Songlines are then used to map the course of their lives.

The specific ancestor is a symbol of the human spirit of each aborigine – it is the place of origin of their souls and symbolizes their nature. An aborigine develops their sense of identity from observing the nature and character of their Dreaming totem. Songlines are then used to map the course of their lives.

As each aborigine grows, they create songlines to explain their past, present or future. The “Songline” is exactly what the name suggests. Each tale is a song, filled with voice, dance steps and ceremonial rituals which are common to all aborigines of the Dreamtime.

The connection with the spirit ancestors was the common bond which tied together all tribes of indigenous Australians.

Prior to settlement in 1788, there were over 1,500 individual aboriginal tribes, with over 750 different dialects. Communication between the different groups of aborigines was based on their links with the Dreaming ancestor. Although the dialects of the tribes varied, aborigines drew upon the array of myths and tales of the Creation Ancestors common to all tribes. Communication was via an aborigine singing their ‘songline’, that would tell a story which represented the motive behind a persons actions or deeds.

It is the duty of each aborigine to communicate with their “dreaming” ancestor. They must declare their deeds and justify their actions to their kindred ancestor;

Through Song, in art.

In dance, through ceremony.

And in life’s acts.

Dreaming Art

The connection between the dreaming and art is of central significance to the Aboriginal people.

As the Dreamtime is a spiritual vision of the creative forces and motives behind all existence, art explains the spiritual life as it appears to the aborigine.

Through art, the spirits of creation, hidden within the world are revealed, and their connection with life on earth is shown.

There is a variety of forms of expression of Aboriginal art. The most common being;

-

Rock Painting

-

Body Painting

-

Canvas painting

-

Bark Painting

DREAMING ARTFORMS

The forms and styles of the traditional aboriginal arts vary in relation to the geographical origins of the artist.

Rock Painting.

Australia contains some of the most outstanding examples of rock art top be found in the world. Significant examples can be found in the Kimberley’s (WA), Arnhem Land (NT) and Cape York, (Qld).

Body painting

Chiefly of ceremonial importance, body painting relates to the ‘dreaming’ of an Aborigine. The design is most often an image of the spirit ancestor. Steeped in ritual, body painting is the image of the connection forged between the people and their spirits.

Bark painting.

Bark painting is traditionally found in the northern regions of Australia, and in particular Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. Bark painting is most often shaped in the distinctive X-ray image style. These X-rays reflect the many levels of existence of the spirit.

Painting on Canvas

Early ion the 1970’s Aboriginal artists began to paint their designs on hardboard and canvas, and to use Western style paint and brushes. Since this time, the exposure and popularity of Aboriginal art has increased enormously through-out the world.

Many aboriginal artists currently hold international acclaim for the techniques, colours and spirit of their works. In the modern period, Aboriginal painting has undergone many changes in character. Traditional art has always been a spiritual expression. But contemporary works reflect the broader social challenges facing the aboriginal culture.

THE MODERN ABORIGINE

The world of the Dreamtime has been under attack since settlement. Since 1788, the Aboriginal people have not only seen their homeland lost to settlement, but they have also had their society and their way of life taken. Generations of aboriginal children have been taken from their families, communities and cultures, and had a way of life imposed upon them.

Recently many Australians, aboriginal and settler, have taken the initiative in building the traditional identity and culture back into the daily life of the people and our history. It will be the greatest tragedy to lose the knowledge and experience of the Dreamtime. Yet through a combination of education and a return to the traditional “Dreaming” life, the native people are building a new sense of pride and joy in life. But what the aborigine does seek is justice.

Justice

For the modern Aborigine is the respect and acknowledgement by all people, of the culture and traditions of a people who for over 40,000 years called this land home.

Most importantly Aborigines seek POSITIVE CHANGE from all Australians in making an effort to understand the Dreamtime society of the native culture of this land. Aborigines seek the right to live in the world of the spirit ancestors, to do honour by their tribe and society, and to live life according to the spirit of the Dreaming.

ABOUT THE DREAMING SERIES

Featuring the art of Robert Campbell junior(1944-1993).

Ngaku Tribe,

Burnt Bridge Mission, Kempsey, NSW.

“When I paint, I don’t make a copy or sketch first. It just comes from within me and I just keep going. I paint about things that touch me personally. It forms a picture in my mind – it’s the spirit in me. It just guides my hand. And that’s the result of it.” Quote:Robert Campbell Junior. (Personal Diaries, 1989)

Robert Campbell jnr. Is an artist of the Ngaku Tribe of Northern NSW.

Today Robert’s work stands at the pinnacle of the modern aboriginal art style, and his contribution to the future of this style is sorely missed since his untimely death.

Robert was born and raised in Kempsey, at the Burnt Bridge Mission, on the outskirts of a country town on the east coast of Australia. Life at the Mission exposed Robert to the vast differences between the two cultures at an early age. Robert was to gain prominence later in life for his vivid portrayal of life for the aboriginal people when the modern Australian culture collided with the traditional lives of indigenous Australians.

Robert’s introduction to art came at the tender age of 6, when he first began to work with his father, Thomas W. Campbell, who at the time was Australia’s foremost boomerang maker.

During this time Robert drew designs for his father’s work – fish, animals and birds. His father would then trace these images onto the boomerang, and use a red-hot wire to burn the shapes in.

From the moment Robert first picked up a brush and painted, his skill and passion for art was obvious to both himself and those around him. Despite his confused and impoverished up-bringing, Robert ceaselessly pursued his appetite for art.

He would often disappear into the bush for days at a time, to gather materials and ignite his imagination to fill his ever-growing number of artworks.

But after leaving school at the tender age of 14, Robert found it hard making ends meet as a young indigenous artist. Many of the settlers in the town of Kempsey had little time or patience for the native inhabitants. As a result Robert was forced to leave his homeland and moved to Sydney, NSW. This was to prove an experience which was to forever change the life of this artist . . .

Robert’s move to Sydney was to prove the turning point in his career. It was the period in his life where Robert first confronted the issues of social inequality and prejudice towards the native Australian people in his painting. It was an experience which had a profound effect on Robert, and clearly influenced his work from this moment forward.

Robert’s social awareness grew enormously at this time. Previously he tended to paint idyllic landscapes but his subject matter soon came to confront prominent social issues which affected him.

From the oppressive forces of racism, land rights, forced re-settlement, to the monotony of life for traditional people without the Dreamtime, Robert pursued social equality within the context of his work.

His upfront style and simplistic vision of social inequalities, put Robert at the forefront of a new sense of self-perception in the indigenous community, often called aboriginality, arising during the 1960’s, 70’s and ‘80’s.

During this time in Sydney, Robert’s talents came to the attention of the artistic community. Through the efforts of Tony Coleing and Roslyn Oxley, Robert was encouraged to paint on canvas and exhibit his works. Success and acclaim rapidly followed.

Robert’s Unique Style

The contribution Robert Campbell jnr. Has made to the development of both native art, and the broad Australian art scene, involves not only the bold way he confronted social issues, but also the unique style he evolved to express his artistic visions.

As a self-taught artist with no formal training, Robert’s style was uniquely his.

Robert constantly aspired to represent the positive spirit alive in all things. By using his distinctive cartoon-like narratives of people and animals in the world, Robert sought to connect the traditional Dreamtime of his people with the forces of modern Australian culture. In essence he hoped to provide a bridge between the reality of society in the western economy, and the spiritual focus of indigenous people.

Campbell is an iconic indigenous artist, who is often referred to as a founding father of the urban aboriginal art style that evolved in the late 1960’s, early 1970’s Australia.

Drawing on the ‘black pride’ movement in the USA, indigenous Australia found a new voice for the Dreamtime culture. A sense of reverence and dignity for their Dreaming culture emerged for the first time since white settlement, and artists like Robert Campbell became a voice for this new movement. Campbell was acclaimed not just for his unique style, but for engaging strong social commentary in his works. But rather than find anger, Campbell sought to build bridges between indigenous culture and modern Australian society. The result was a style that was accessible, vibrant and witty.